Four Things We Must Change (to change the world)

We need to change some things if we want to change the world.

I see four distinct items in New York State public work delivery that need our attention if we are to get the building projects we not only deserve, but that we need for a vibrant, successful, resilient future.

- we need to change our procurement to allow for the current speed of innovation

- we need to engage more with contractors in design and in successful relationships during construction

- we need to change our payment structures in design to value performance, not final construction costs

- we need to base state projects on Total Cost of Ownership in order to make wise design decisions

If we want innovation we have to allow for innovation to occur. Currently, when we do public work in NY, state procurement law requires we specify products that have three “equals” in the market. Call me crazy, but if there are three equals out there, the product, tech or service is not innovative, it is merely state of the art. NREL (national renewable energy labs) addressed this in their recent zero net energy projects by using the “equal” qualifier in the procurement of the design and construction team. They then they allowed sole source products, technologies, and services under that contract as needed to innovate and achieve the performance goals of the project.

If we want innovation we have to allow for innovation to occur. Currently, when we do public work in NY, state procurement law requires we specify products that have three “equals” in the market. Call me crazy, but if there are three equals out there, the product, tech or service is not innovative, it is merely state of the art. NREL (national renewable energy labs) addressed this in their recent zero net energy projects by using the “equal” qualifier in the procurement of the design and construction team. They then they allowed sole source products, technologies, and services under that contract as needed to innovate and achieve the performance goals of the project.

If we want collaboration we need to support it. There are several pieces of this.

Avoid the creation of adversarial relationships –

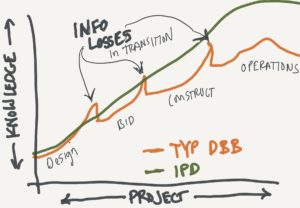

Currently, most public projects in NY must use a process of design/bid/build, and this process creates adversarial relationships that can, and often do, deteriorate the quality of the work and product.

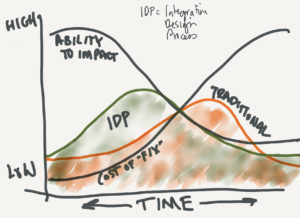

We have the A+E team (typically) design the project based on owner goals and current site/existing building conditions. On complex projects, the people creating the documents (drawings, specifications, contracts) for bid can number near 1,000 stakeholders, design professionals, surveyors, energy modelers, specialty designers, product reps, lawyers, owners, and budget analysts. And none of these involved people can be the contractors who may eventually work on the project. Once we put the Bid Documents out “on the street” we allow 2-3 weeks for the contractor, who has never before seen this information, to understand the design, assess their own capabilities and schedules, and price the work. And we reward the bidder who delivers the cheapest price by giving them the job. We do not award the job to the bidder with the most accurate price.

This poisons the project from the start of construction as the contractor is immediately forced to try to make up the losses s/he had to enfold into the bid to win the work. Making up these losses can include combing the documents for missed items and putting in change order claims, taking shortcuts in construction, or putting unskilled, less expensive, day labor on the job as often as possible.

We could change our bid process. I have heard of bid processes that are public and still keep separation between design and construction, but select the winning bid as follows: throw out the highest bid, the lowest bid, average the rest and select the bid closest to the average. This means all bidders are trying to price to the most real price and we don’t reward a contractor for bidding low just to get in the door on the work.

Find a way to pull construction knowledge into the design process –

The insights of the contractor are not accessed during the design process, and this can adversely affect price, schedule, and success in the building phase. If the design calls for a familiarity with a material that the local builders have never before seen, as occurred often in the earlier days of using Hardie-plank for siding in rain screen building envelope designs in the upper NE, we can incur poor installation, or significant mark-ups in labor or material costs. We are also missing out on learning what skills could be brought to beneficially bear on the design. Maybe the contractor has experience with a panel system the architect is not familiar with, and that knowledge could inform the design choices for improved performance and speed in construction even while improving sustainable goal achievement.

Some public projects in NY now allow design-build which is one good step toward improved collaboration with the construction entity, however this method currently has limited application in public work, and there is concern that the structure of this relationship in NY allows the contractor to lead the contract, putting the architect in an untenable position related to their professional responsibility. In brief, if you, the architect, have a salary paid by the contractor, and a code issue comes up, will you stand firm to correct that issue even if it puts your job at risk? Maybe not even though your professional credentials require you to do so. A better approach would be for true partnership or for the architect to have a 51% role as partner.

Design-build is not the only way. Other ways of integrating some level of construction knowledge into the design work exist, such as construction management (CM) involvement early in the project, CM at risk, or through a service entity, such as a design and construction oversight entity in government, increasing their in-house construction expertise involvement during design phase. Another would be to use IPD (integrated project delivery) which is a contractural approach to creating a team that shares risk factors and ensures inputs from the construction into the work.

If we want high performing buildings, we need to make sure our fee structures support it. On the design side we have a fee structure that makes breaking from our past design solutions difficult. When we hire MEP consultants, often we base their fee on the construction cost of their final system design, yet in high performing buildings we are trying to minimize the mechanical systems at least, or even totally redefine what and how much is needed. To do this takes a lot of talent, attention, and effort. We are asking our professionals to work harder for less money.

A solution to this could be basing fee on performance of the final product, or perhaps creating an incentive fee when a the project achieves a certain level of achievement. The human response to reward is powerful. We pay people a reasonable design fee, shared in an equitable fashion between all design participants, then put a pretty carrot out there for the achievement of zero net energy, or for a design solution that is further assessed to inform all fixture similar work by that state. This could prove inspirational and transformational as a win/win scenario. What would happen if we approached all new and renovated building projects in this way?

If we are aiming for high performance, we need to make design decisions based on goals for that performance. Total cost of ownership (TCO) is my final “big issue” in state work. As in many other arenas, our capital investments are totally separate from our operational budgets. This leads to: deferred maintenance that cripples institutions and forces expensive rehabs or demolition of facilities well part rescue, glitzy wow-em projects with no operational plan in place, cheap energy system implementations with no thought of replacement costs, and a total lack of awareness of fuel choices in design.

If we were to unite the capital budgets with operational dollars, we could make the “additional” investments up-front in design that would save money over the life of the building. We could choose durability. We would be encouraged, as the design team, to assess buildings after a year of operations, after five years, and to fold that knowledge into the design of future buildings. We would be compelled to move into a continual improvement mentality in our work and in facility management. This would be even more powerful if the TCO included personnel cost considerations to amplify the importance of good air quality, healthy materials, and connections to nature.

Furthermore, the market would begin to realize the importance of products and tech that are easily reparable and maintained over a long life of use, or designed for discreet plug-in-play replacement and including integral recycling and remanufacturing plans. And they could provide the service plans for both of these derivatives as a value-add to their business services. We are seeing some of this already in the electric vehicle market, and in technology items such as phones.

In summary, if we are to design for our high-performing future, including sustainability, resiliency, climate change mitigation and adaptation, materials management, support of health and productivity along with safety of the humans in our buildings, beauty, usability, durability, and community engagement (yes, these are all part of good design and construction projects) we need to change a few things. These few things are of increased importance for public benefit projects, supported by taxpayer dollars.

I suggest we change these four aspects of design and construction process and contracting. Quite simply, to change the world of public benefit projects, and beyond. They are not easy to alter, but the benefits are clear.

Jodi, getting serious about getting greener.

2 Others like this post, how about you? (no login required)